student debt

Obama hits the Bulls Eye with the Student Debt Forgiveness Program

Almost 33 percent of the professional workforce in USA has taken student loans at some point of time in their academic career. The student loans have become the norm of the current education system. It is more so because of the initiatives taken by President Barrack Obama to replenish the federal system with more career-oriented citizens and service-driven public officers. The last couple of decades have been very harsh on the American education. The volume of immigration has increased and the students in USA now belong to more ethnically diverse backgrounds. Moreover, the number of wars fought in the last 10 years has put the education system on the back-burner. In order to give a boost to the public services, Barrack Obama has played a maser-stroke to encourage the students to take availing student loans to focus on education.

Not long ago, and to some extent even today, students who availed the loan service could not manage to repay the whole amount as per the schedule. It leads to garnishment of wages, confusion in the expenditure budget and also pushes the person to look out for double employment. Double employment is still considered as unethical in certain parts of the world. In USA, double employment can lead to IP infringement moves and can also lead to clash of business interest. It is a double whammy for the students who wish to avail the student loan but have no backing from the government. The Student loan forgiveness program announced by Obama has definitely helped in shifting the focus away from debt ridden economy to restricting the link between education and financial services.

In the last 2 years, the students who availed the loans for education benefited largely from the loan forgiveness programs linked with Obama Student Debt Forgiveness scheme. The program helps the students to bargain time and spread their debt sum over a longer period of time with superlative backing from the agencies.

The star pointers of the program are:

- With a relatively extended time to repay your debt amount, chances of maintaining a clean credit record are so easy.

- The agencies guide the students to plan their repayment schedules so that they don’t end up being inducted in to’ Hall of shame’ of non-payers.

- The repayment sum is linked to income. The loan agencies know the exact financial condition of the debtor at all stages of loan forgiveness program.

- The flexible rates can be availed as per the debtor’s requirement. You can now consolidate the interest rates with other loan amount you may have taken earlier or are planning to take shortly.

- It encourages the employment of public servants who have their loan sums forgiven after 10 years of continuous employment. Only condition that comes with the scheme is that you would have to pay the interest sum regularly on schedule without missing out the deadline ever in the 120 months of loan repayment.

- No garnishment of wages once you are forgiven. Your record is wiped clean fromthe debtors list.

Now, you can actually plan your education far more effectively and need not worry about the repayment of loans for at least 25 years.

The Scary Side of Student Debt

Defaulting on your loans can ruin your financial life. Here are some good strategies to avoid or repair the damage.

Imagine going to college to improve your life and walking away with $500,000 in student debt. That number is no typo. A young Seattle couple ended up so mired in debt on the way to their degrees that they “couldn’t even make the initial payments,” says Christina Henry, of Seattle Debt Law. After the collection agencies started calling, the couple, who have two children and earn a total of $80,000, visited Henry for help. “They took out as much as they were able to and didn’t even know how much they had. It’s the most egregious case I’ve ever seen.”

Imagine going to college to improve your life and walking away with $500,000 in student debt. That number is no typo. A young Seattle couple ended up so mired in debt on the way to their degrees that they “couldn’t even make the initial payments,” says Christina Henry, of Seattle Debt Law. After the collection agencies started calling, the couple, who have two children and earn a total of $80,000, visited Henry for help. “They took out as much as they were able to and didn’t even know how much they had. It’s the most egregious case I’ve ever seen.”

Consider it a cautionary tale. Over the past decade, college students have had every reason to borrow for college and little reason not to. College costs exceeded inflation by as much as six percentage points a year, bringing the average annual price of a private-school education to $37,000. Congress raised the maximum on federal student loans and introduced the Grad PLUS loan, allowing graduate students to borrow up to the cost of attendance. And until 2008, when credit began tightening up, lenders handed out private student loans as if they were party favors.

Result? More students borrowed, and in larger amounts. The average debt at graduation was $24,000 in 2009, up 6% from the year before, according to the Project on Student Debt. But that understates the dramatically higher debt that some students racked up. And many of them got swamped by their bills almost immediately. Of the 3.4 million federal-loan borrowers who entered repayment in 2008 (as the economy slid into recession), 7% defaulted within the year, the highest percentage in more than a decade (see the explanation of late-payment penalties below). That statistic doesn’t include the thousands of borrowers who fell behind on their payments without defaulting, or those who couldn’t keep up with their private student loans.

Missing a few payments invites dunning calls and letters, but defaulting has the potential to destroy your future. Being on the dark side of federal student debt means the feds can demand payment in full, assign your case to a collection agency, garnish your wages, pocket any state or federal refunds, and even come after your benefits in your old age. “We see people who defaulted on loans in the 1970s and 1980s whose Social Security benefits are being garnished,” says Paul Combe,of American Student Assistance, an agency that guarantees federal loans. Worse yet, old, neglected loans carry decades’ worth of fees, interest and collection costs. “A $2,000 loan that defaulted 20 years ago is now $30, 000,” says Combe.

The federal loan program offers several plans that can get you back on track. With private loans, you have to negotiate with the lender. Either way, start by knowing what types of loans you have, where they originated and who services each one. For federal loans, go to the National Student Loan Data System.

For private loans, review your loan agreements, which should include the terms of the loan and repayment options.

Help with federal loans. With the federal loans known as Staffords (now part of the Federal Direct Loan program), as well as Grad PLUS loans, the loan goes into delinquency when your payment is 21 to 30 days late. If you fall 60 days behind, the loan agency will report the lapse to the national credit bureaus. Meanwhile, late fees and interest will add up.

If none of the federal repayment programs offers a solution, apply to your lender for deferment or forbearance. Deferment lets you forgo monthly payments, usually for a year at a time, for up to three years. The feds pay the interest on subsidized Staffords but not on unsubsidized loans.

Accrued interest gets tacked on to the principal. You have a legal right to deferment if you meet certain criteria, including economic hardship or status as a half-time student or you are on active duty in the military.

Forbearance gets you off the hook on payments for up to five years, in yearlong increments. Generally, the lender decides whether you qualify. Interest accrues on all the loans, including subsidized Staffords. Forbearance makes most sense for borrowers who are experiencing a short-term financial crunch, not those whose situation is unlikely to improve. Such borrowers are better off in an income-based plan, which can reduce the payments to as low as zero and offers forgiveness after 25 years.

Defusing Default

If you fail to make a payment for more than 270 days, your loan is technically in default, but most lenders wait 360 days to make the default official, giving you a window in which to redeem yourself. (If you’re in that phase, call your lender immediately to discuss your options.) After the loan defaults, you lose access to forbearance and deferment, as well as to future federal student aid, and the default goes on your credit record.

Uncle Sam gives you several ways to get back in his good graces. One is to rehabilitate the loan, in which you contact your lender and arrange to make nine timely, “reasonable and affordable” payments over a ten-month period. The Department of Education sets guidelines as to what constitutes reasonable and affordable and stipulates that the lender can’t require a minimum payment. In practice, however, negotiating the amount with the lender can be “a huge problem,” says Deanne Loonin, of the National Consumer Law Center. If you rehabilitate your loan, the default disappears from your record.

The other strategy is to consolidate your loans with the Federal Direct Loan program, which lets you immediately enter one of the income-based repayment programs. (If you have already consolidated your loans in the Direct Loan program, you generally are not eligible to do so again.) “The advantage of consolidation is that it’s faster. You don’t have to make nine payments first,” says Loonin. But the default remains on your credit record for up to seven years.

You may conclude that your debt is simply insurmountable and decide to try for bankruptcy. To succeed, you must demonstrate to the court that your payments impose “undue hardship,” with no prospect of remedy, and that you made a good-faith effort to repay.

In a few circumstances, such as death or permanent disability, or if the school closed while you were enrolled, your federal loans are eligible for cancellation.

Help With Private Loans

Lenders of private student loans typically consider you to be in default as soon as you blow past the payment period, and you can count on receiving collection calls shortly thereafter.

To avoid that scenario, some lenders allow you to make lower payments for a few years and catch up later. They may also grant you forbearance, for three months at a time, during which interest continues to accrue. But don’t expect them to go out of their way to extend these deals, says Loonin. Check your promissory note. If you don’t see an alternative plan, call the lender and try to arrange one.

Unlike the federal government, which can garnish your wages and pursue the debt indefinitely, lenders of private loans must sue to collect on a default, and they are subject to your state’s statute of limitations, usually six years. Lenders can and do take borrowers to court, says Loonin. “We’ve seen more-aggressive collection efforts, including more lawsuits, on the private-loan side.”

If they succeed, they can garnish your wages, put a lien on your house and tap into your bank account. As with federal loans, private loans are extremely difficult to discharge in bankruptcy and require that you meet the same stringent standards. But a lender might consider settling the debt when the prospects for full payment are dim, says Henry. That was the case for her Seattle clients. With no chance of repaying the entire amount, the couple settled some of their private loans, arranged an income-based repayment plan on the federal loans and hope to discharge the remaining debt in bankruptcy.

RESOURCE OF ARTICLE: http://www.kiplinger.com/article/spending/T053-C000-S002-the-dark-side-of-student-debt.html

These 9 Charts Show America’s Coming Student Loan Apocalypse

Borrowers with federal student loans, long promoted as the safest way to borrow for college, appear to be buckling under the weight of their debt, new data show.

More than half of Direct Loans, the most common type of federal student loan, aren’t being repaid on time or as expected, according to figures from the U.S. Department of Education. Nearly half of the loans in repayment are in plans scheduled to take longer than 10 years. The number of loans in distress is rising.

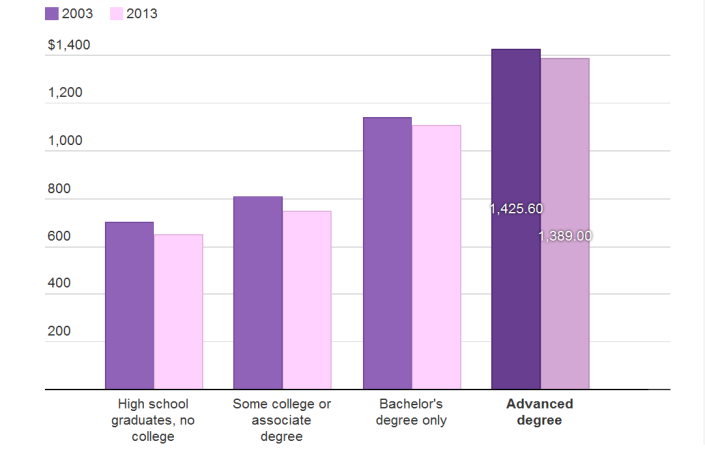

The increase in troubled loans comes as the average amount of student debt has significantly outpaced wage growth. After adjusting for inflation, the average recipient of federal student loan funds owed 28 percent more in 2013 than in 2007, according to Education Department data. But the typical holder of a bachelor’s degree working full time experienced a 0.08 percent decrease in weekly earnings during that same period. For those with advanced degrees, median wages increased just 0.02 percent, according to figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Obama administration, mindful of borrowers’ difficulty in repaying their federal student loans, has been promoting repayment plans that cap monthly payments relative to income. An unemployed borrower with no income, for example, could pay nothing every month, yet still be considered current on the debt.

At a December Education Department conference in Las Vegas, Brian Lanham, then an executive at student loan giant Sallie Mae, said that more than 40 percent of borrowers who enroll in so-called income-driven repayment plans have a zero monthly payment.

It’s “something that’s really boosted our income-driven repayment application rates,” Lanham said, according to a recording of the event the department posted on YouTube. “If they’re struggling,” he said of borrowers, “it’s an option.”

The Education Department did not respond to inquiries regarding the number of borrowers enrolled in plans that require them to pay nothing to keep current on their loans. Patricia Christel, a spokeswoman for Navient, the former Sallie Mae servicing unit that has since become an independent company, did not respond to requests for comment.

Unpaid debts are typically forgiven after 20 to 25 years of repayment in income-driven plans. Some critics worry that too many borrowers are enrolling in income-linked plans, forcing taxpayers to foot the bill.

For the past few years, policymakers and regulators responsible for safeguarding the nation’s economy and financial system have been warning about dangers rising student debt pose to economic growth and household balance sheets. Borrowers who devote bigger chunks of their paychecks to repaying student loans may be less likely to buy a house, stunting the housing recovery. They also may be less likely to save for retirement, putting more strain on Social Security, or start a small business, which typically creates new jobs and boost economic activity.

The Education Department released data this month providing a much more detailed snapshot into how borrowers are coping with their federal student loans and how the government’s handpicked loan companies are juggling their obligations to borrowers and taxpayers. The charts below are based on that data, as well as other sources that complement it.

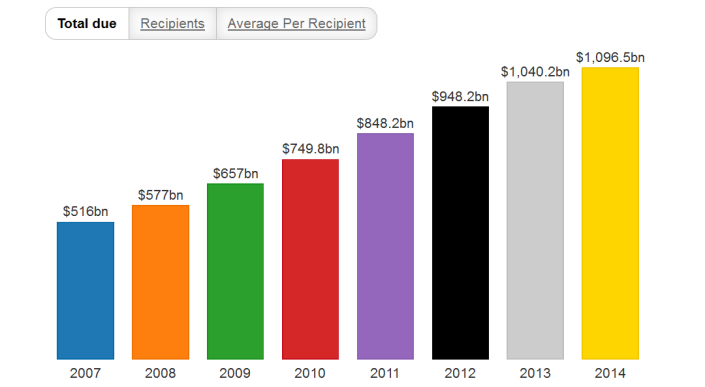

Outstanding Federal Student Loans

Annual figures as of Sept. 30. 2014 data as of June 30.

Wages Fall Amid Rise in Student Loan Debt

Median inflation-adjusted weekly earnings for full-time workers at least 25 years old

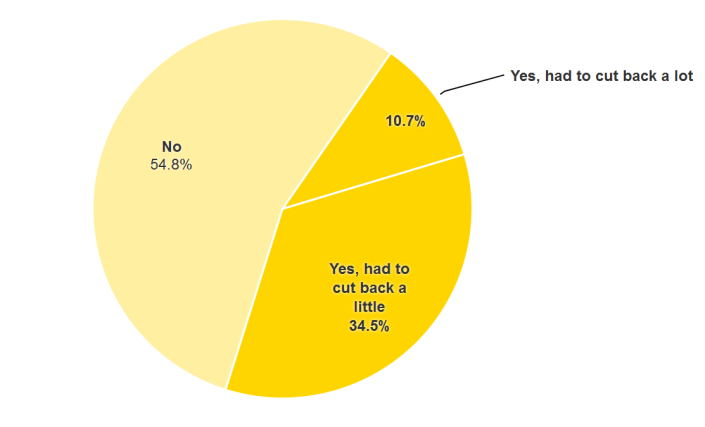

With student loan debt rising and wages falling, borrowers with all types of student loans are cutting their spending to make loan payments.

Over the past 12 months, have you had to cut back on any spending so that you could make your monthly student loan payment?

Survey based on 586 respondents. From “Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2013.”

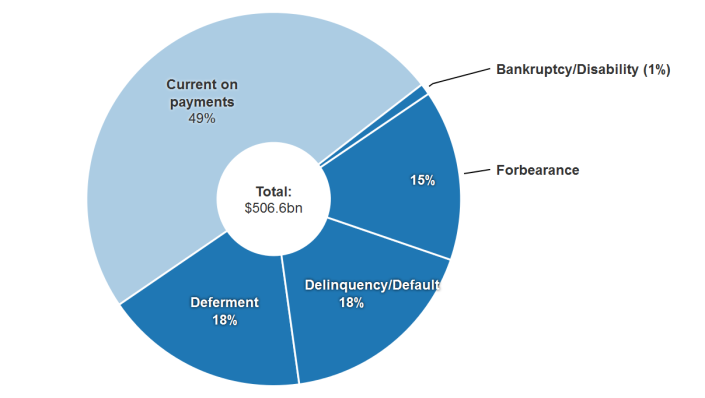

A large share of borrowers are in deferment or forbearance plans, which enable borrowers to delay full monthly payments. Both are meant for borrowers experiencing some kind of financial hardship, such as unemployment, illness or a temporary inability to repay. Borrowers returning to school for advanced degrees typically receive a deferment for loans incurred as undergraduates. Deferments for up to three years also may be granted to borrowers experiencing unemployment or an inability to find full-time work.

Borrowers Struggling To Make Payments

Excludes loans in grace, in-school status. 51% of borrowers are not repaying loans on time, as expected. As of June 30, 2014.

There’s little public data that details borrowers in deferment or forbearance who are postponing payments due to graduate school or military service, for example, versus financial hardship or unemployment. A 2006 Education Department study found that borrowers who used deferment or forbearance were more likely to default on their federal student loans. Deferment and forbearance also were linked to bigger loans.

“The problem is we don’t know who is deferring for what reasons because the Department of Education won’t release that data,” said Robert Kelchen, a professor at Seton Hall University who specializes in higher education finance. “Some may be in there for what we consider good reasons — for example, military service or the Peace Corps.”

Last week, an Education Department spokeswoman said data detailing reasons for deferment weren’t readily available and may take weeks to assemble, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education.

“But the Education Department should know,” Kelchen said. “They should have the data. They just haven’t put it together for the public to use, which is a problem.”

The underlying problem, Kelchen said, is that the National Student Loan Data System, the Education Department’s central database for student aid, “is by all accounts a really lousy system.”

As of July 2013, the system had 28.9 billion active and historic records for 82.1 million students who combined had nearly 371 million loans and 116 million grants, according to federal procurement records.

The lack of public data has fed skepticism among borrower advocates, who claim the Education Department’s loan servicers routinely place borrowers in forbearance plans rather than enrolling them in income-linked plans. Enrollment in income plans requires servicers to verify borrowers’ incomes. Granting a forbearance requires little work.

In November 2012, Cynthia Battle of the Education Department told financial aid administrators that deferment and forbearance “should not be the first option,” according to a copy of her presentation.

In July 2013, John Remondi, the chief executive of Navient who was then Sallie Mae’s top executive, told investors that it was “very expensive work” to enroll borrowers in income-linked repayment plans.

That same month, Battle and Sue O’Flaherty of the Education Department told financial aid administrators that the department had discovered that some borrowers were on forbearance plans for extended periods, prompting the government to limit forbearances. They added that loan companies should highlight income-driven repayment plans when talking to borrowers before granting a forbearance, according to their presentation.

Borrowers Getting Help vs. Those That Need It

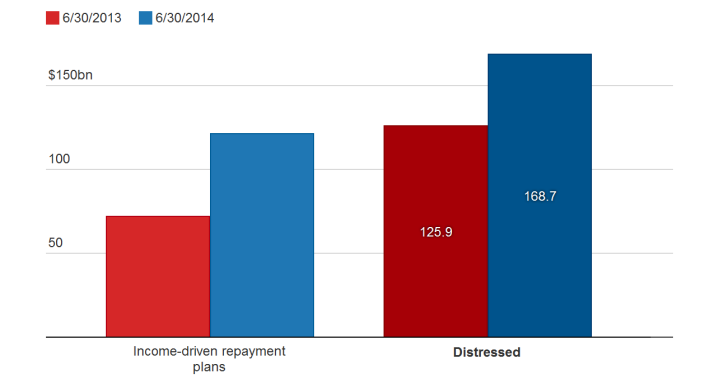

Direct Loans. Distressed loans defined as being in forbearance, delinquency, default, or bankruptcy. Some loans in forbearance, delinquency may be in income-driven plans.

The message appears to have gotten through to the department’s loan servicers. Among Direct Loans, which comprise nearly two-thirds of the $1.1 trillion in unpaid federal student loans, enrollment in income-linked plans has increased 68 percent over the past year.

The jump came after a June 2013 survey for the Education Department that found that 54 percent of new borrowers who were less than six months out of school didn’t consider the most popular income plan — Income-Based Repayment — because they didn’t have enough information, according to Ed Pacchetti, a department official who discussed the findings during the department’s December 2013 conference in Las Vegas. A recording of his remarks is on YouTube.

Some 44 percent of surveyed borrowers who were less than six months out of school, or in “grace” status, said they had not been contacted “at all” about their loans, Pacchetti added. The previous November, Battle said most borrowers who had defaulted did not receive their full six-month grace period due to “late or inaccurate enrollment notification” by their school.

Education Department data suggest that schools and servicers have improved their outreach to borrowers.

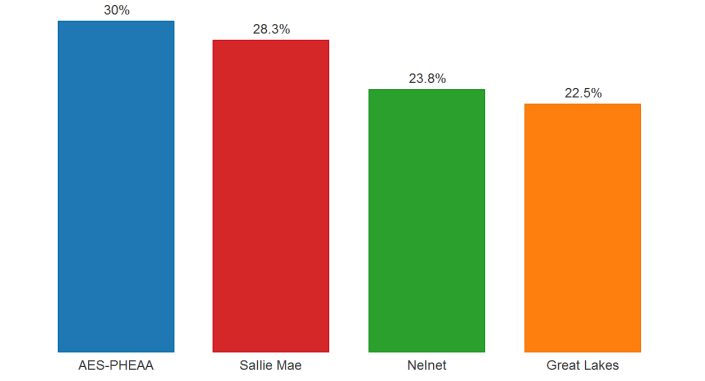

Share of Loans in Income-Driven Repayment Plans

As of June 30, 2014. By dollar amount. Excludes uncategorized loans.

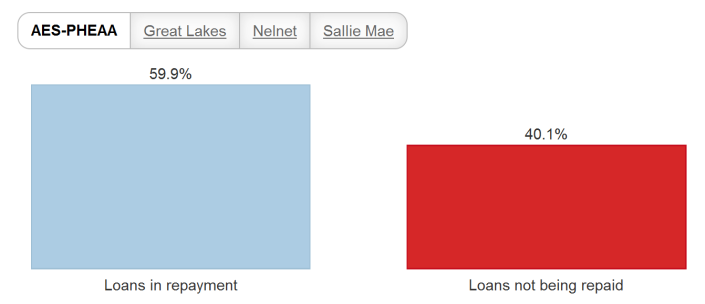

Share of Loans Being Repaid

As of June 30, 2014. By dollar amount. Excludes loans in grace, in-school status.

According to Kelchen, the mere presence of income-linked repayment plans “in theory” should result in a zero delinquency and default rate. Increased enrollment in income plans should reduce the ranks of future troubled borrowers, he said.

In April, Sarah Bloom Raskin, deputy treasury secretary, questioned why some 7 million borrowers have defaulted on their federal student loans, given the availability of income-linked repayment plans.

Raskin, the Treasury Department’s second-ranking official, challenged the Education Department and its loan specialists over how they handle borrowers struggling with student debt.

Education Department data suggest that while borrowers may be better informed about their options when it comes to income-linked plans, far too many aren’t being properly counseled by their schools’ financial aid administrators and the government’s loan servicers when it comes to picking repayment plans.

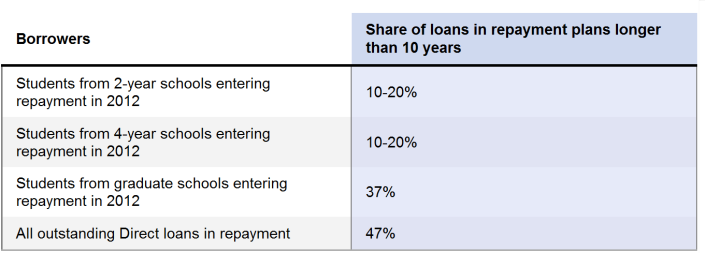

New Borrowers’ Expectations vs. Reality

Direct Loans data excludes uncategorized, alternative repayment plans. Recent borrowers’ data from March 2014 Gainful Employment proposal.

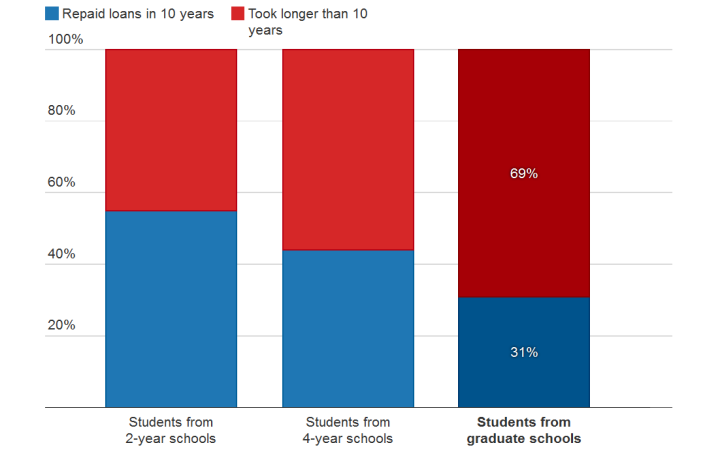

The vast majority of former students entering repayment on their federal student loans in 2012 picked 10-year plans. The numbers were higher for former students from two- and four-year programs, up to 90 percent of which picked the standard 10-year plan.

Good Luck Repaying Your Student Loans in 10 Years

Borrowers entering repayment in 2002

Recent history indicates that many of those borrowers will be repaying their federal student loans for far longer than 10 years. With a lackluster economy, tepid wage growth and vast numbers of Americans still looking for full-time work, some federal policymakers fear current borrowers will need more time to repay their loans than previous generations.

“The concern is that money used to repay student loans are not going into building one’s assets,” Kelchen said. “If you’re graduating at 22, it’s not as much of a concern. But if you’re graduating at 35, that’s money that instead could be going to your retirement.”

The larger fear, Kelchen said: “Will we have a generation of people who hit age 65 or 70 without any assets?”

RESOURCE OF ARTICLE: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08/20/student-debt-distress_n_5682736.html?ncid=txtlnkusaolp00000592

Grad Students Driving the Growing Debt Burden

Report’s Findings Could Reframe Debate on Americans’ Growing Burden

The surge in student loan debt in recent years has been driven disproportionately by borrowing for graduate school amid a weak economy and an open spigot of government credit, according to a report that raises questions about the broader debate about how to resolve Americans’ growing burden.

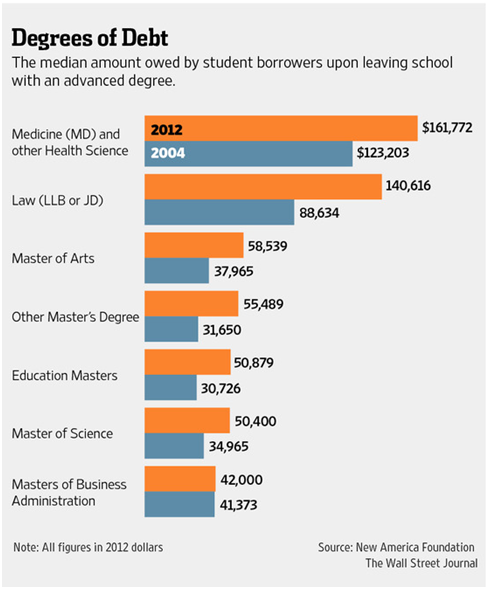

The typical debt load of borrowers leaving school with a master’s, medical, law or doctoral degree jumped an inflation-adjusted 43% between 2004 and 2012, according to a new report by the New America Foundation, a left-leaning Washington think tank. That translated into a median debt load—the point at which half of borrowers owed more and half owed less—of $57,600 in 2012.

The increases were sharper for those pursuing advanced degrees in the social sciences and humanities, versus professional degrees such as M.B.A.s or medical degrees that tend to yield greater long-term returns. The typical debt load of those earning a master’s in education showed some of the largest increases, rising 66% to $50,879. It climbed 54% to $58,539 for those earning a master of arts.

By comparison, the typical student-debt burden of borrowers leaving school with a bachelor’s degree climbed 39% over the same period, to $27,000 in 2012.

The report, to be released Tuesday, shows how much of the increase in student debt over the past decade has been concentrated in a minority of students. In the 2012-13 academic year, graduate students accounted for about 1 in 6 student-loan recipients but between 30% and 40% of student debt extended by the federal government.

Policy makers and student advocates are increasingly concerned about students who leave school with high debt and can’t find work, and then fall behind on payments. That damages their credit and can limit purchases of homes, cars and other items that drive economic growth.

John Berg, a 34-year-old father of three in Safety Harbor, Fla., amassed more than $150,000 in student loans—mostly from the federal government—to obtain a master of arts degree in psychology followed by a doctorate.

The degrees helped him secure a job with the Department of Veterans Affairs as a psychologist, starting out at $68,000 a year. But he said the $1,000 monthly payment will impede his ability to buy a home for years. “I don’t have enough money to save up for my down payment,” Mr. Berg said. “It all goes to loans.”

The report comes as the Obama administration takes steps to reduce student-debt burdens and crack down on career-training schools—mostly for-profits—whose former students are defaulting on loans at exceptionally high rates. People with graduate degrees default on student loans at lower rates than those with lower education levels.

The New America Foundation’s report, along with other data, shows the biggest drivers of student debt in recent years have been costs linked to for-profit schools and graduate schools, said Jason Delisle, the study’s author. “Graduate schools have essentially found a way to capture more of someone’s future income and future spending than what would probably occur if we had some sort of underwriting standards and loan limits,” Mr. Delisle said.

The nation’s student debt—and the rising number of defaults on those loans—wouldn’t seem alarming if debt held by students at for-profit and graduate schools were excluded, said Mr. Delisle, a former Republican congressional aide. “If you factor those two things out, things don’t look very bad,” he said.

The group has, among other recommendations, called on the Obama administration to place tighter limits on how much student debt it forgives as part of an income-based repayment program.

The report is based on federal Education Department data released in the fall that offered a broad look at indebtedness among all students in higher education. The debt figures are released once every four years.

Numerous factors are driving the increase in student debt. Many households lost savings and other assets during the recession, prompting more students to borrow. Schools have raised prices, citing cuts in state aid. And a greater share of students are pursuing advanced degrees than in previous generations to gain new skills and adapt to a modern economy.

The foundation’s report also points to a 2006 law that removed a limit on how much graduate students may borrow from the federal government. Before the change, graduate students—excluding medical students—could borrow no more than $138,500 total for their education and were limited in how much they could borrow annually. Now they can borrow up to the “cost of attendance,” a figure that includes tuition, books, transportation and living expenses. Undergraduates still face a lifetime borrowing cap, currently $57,500.

More graduate students are taking on debt loads approaching six figures. One in four borrowers who earned a graduate degree in 2012 owed at least $99,614 in student loans. Eight years earlier, the top quartile of borrowers owed $70,907 in 2012 dollars.

In 2012, one in 10 students leaving school with an advanced degree owed at least $153,000 in student debt, far above the previous borrowing limits.

Debra Stewart, president of the Council of Graduate Schools, a trade group, said the rise in student debt partly reflects cuts in state funding that are forcing schools to raise prices and students to borrow more. But she said most borrowers will see a return on their investment in the form of higher lifetime earnings.

Workers with advanced degrees tend to earn much more and are less likely to be unemployed than those who have less education. “There’s an undeniable payoff…in economic growth and innovation and job creation,” Ms. Stewart said, though she added that the rise in student debt is still a concern. “For individuals, there’s absolutely no question that graduate degrees are associated with higher salaries.”